"...one suspects nothing artful from the outside, and goes within by the single door that shows itself; and then, after advancing to the farthest interior, and viewing the cunning spectacle, and examining the construction so skillfully contrived, and full of passages, and laid out with unending paths leading inwards and outwards, he decides to go out again, but finds himself unable, and sees his exit completely intercepted by that inner construction which appeared such a triumph of cleverness."

(Gregory Thaumaturgus, Panegyric on Origen, pp. 68–75.)

/Project description continues below the photos/

A maze, the Merriam-Webster dictionary tells us[1], is a noun denoting:

1a: a confusing intricate network of passages

1b: something confusingly elaborate or complicated

2: chiefly dialectal: a state of bewilderment

The word, we discover in Wiktionary [2], comes from the “Middle English mase, from an aphetic variant of Middle English masen (“to perplex, bewilder”); or perhaps from Old English mæs (“delusion, bewilderment”); akin to Old English āmasian (“to perplex, confound”), Icelandic masa (“to chatter”)”

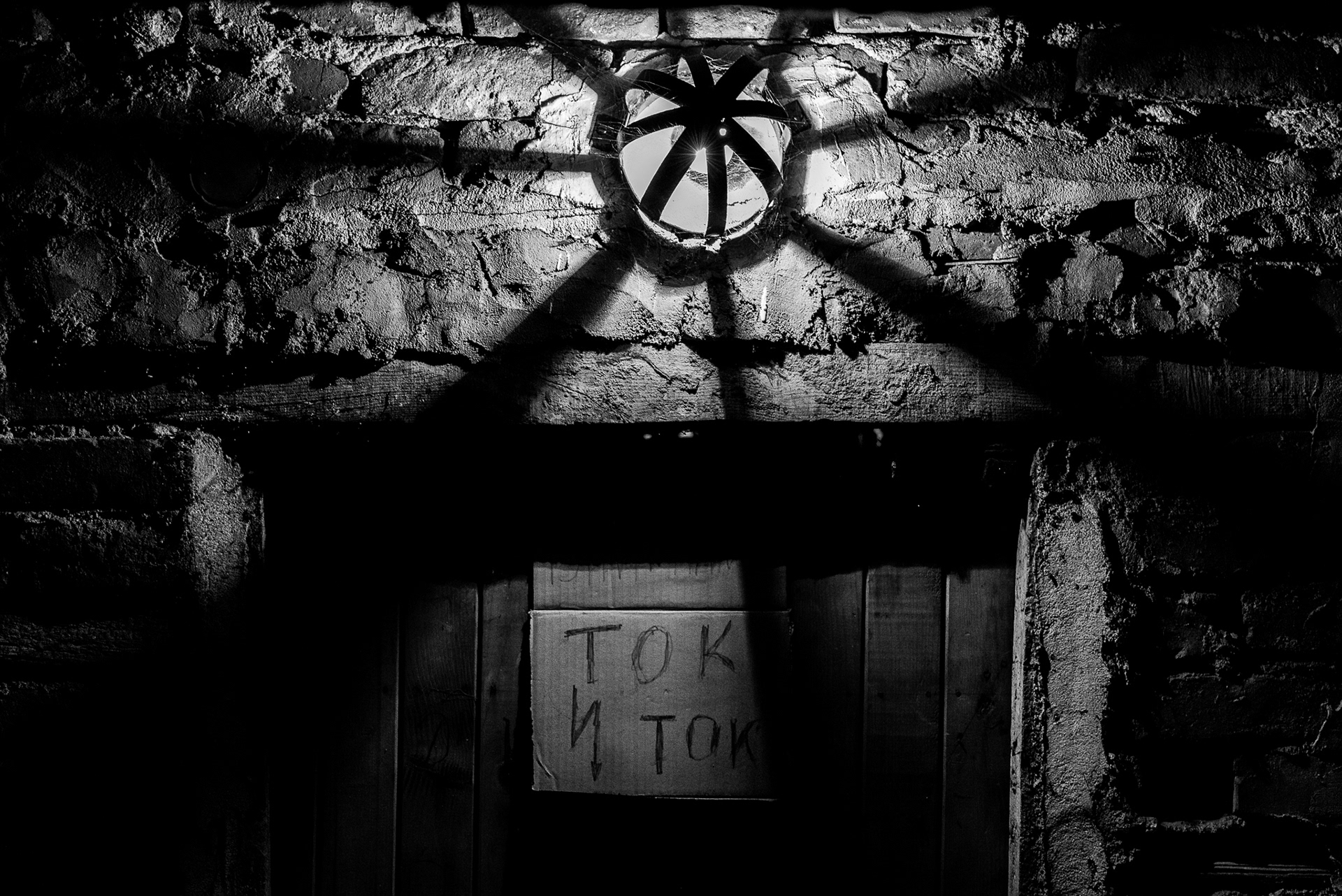

What neither the Merriam-Webster dictionary, nor Wiktionary, can do is enlighten us of an ironic coincidence involving mazes. As faith would often have it, the English word shares the same sounds and identical letters [3] with the Bulgarian word for a fittingly perplexing and confusingly intricate and elaborate object—a ‘мазе’, or what in English is a basement or a cellar.

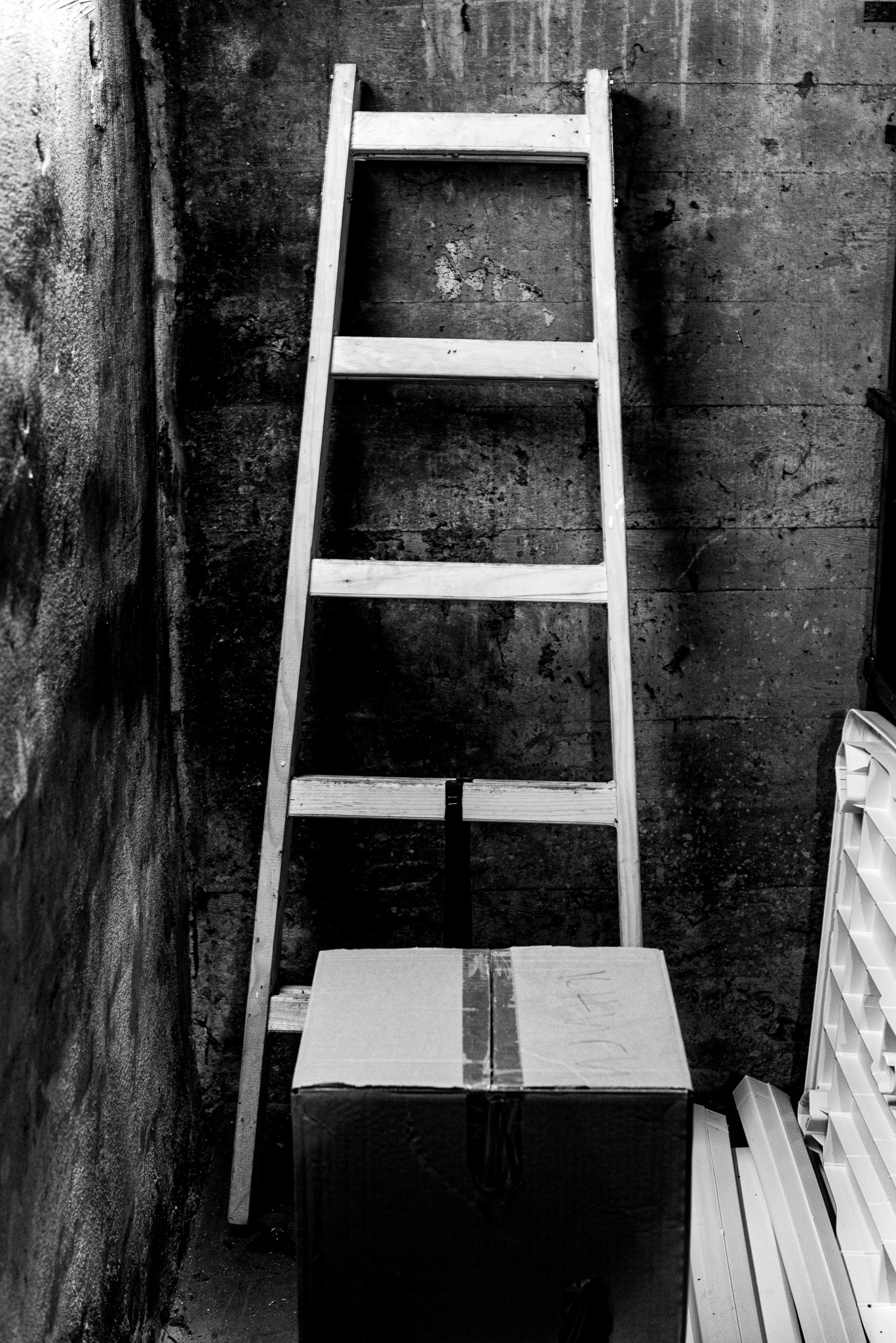

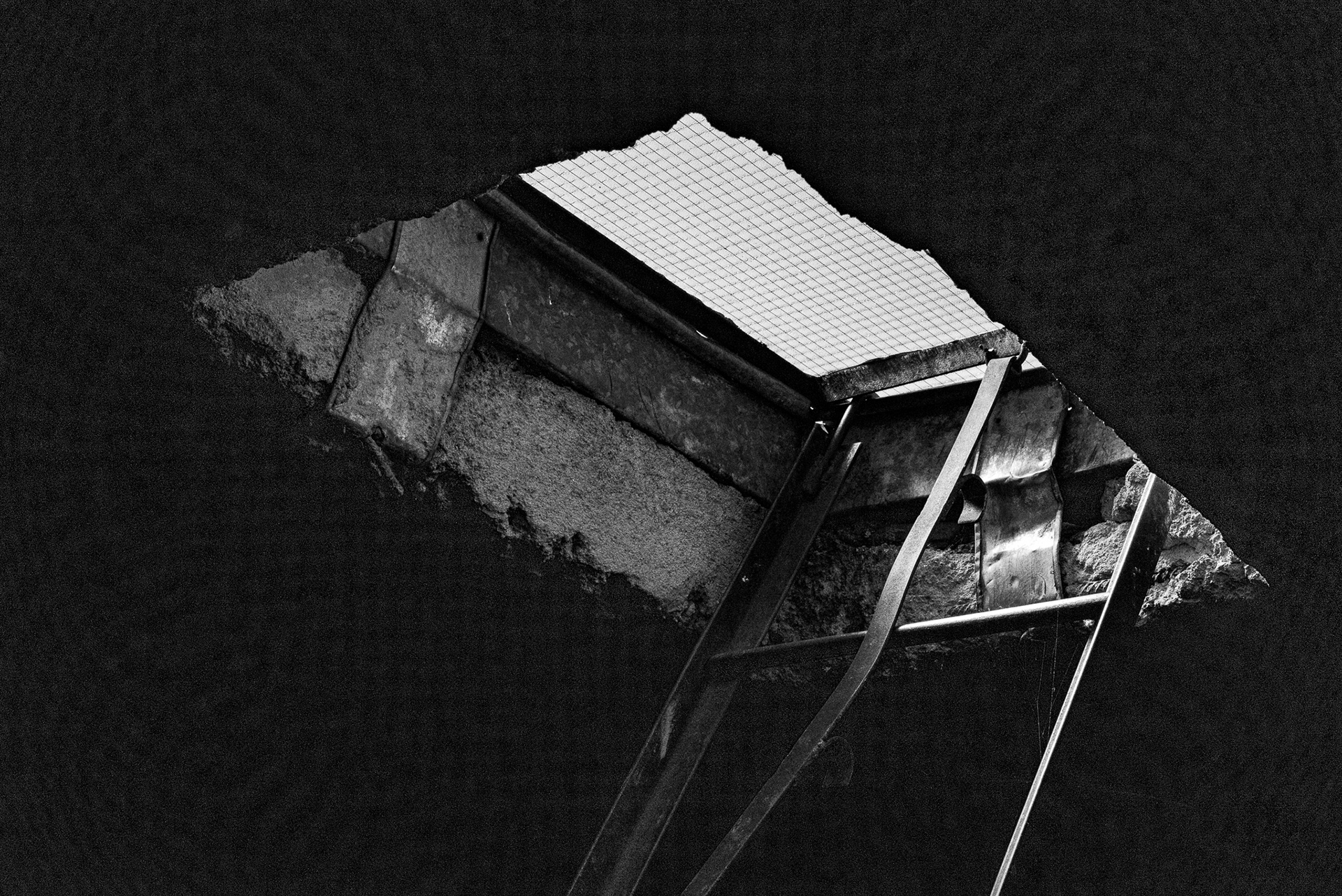

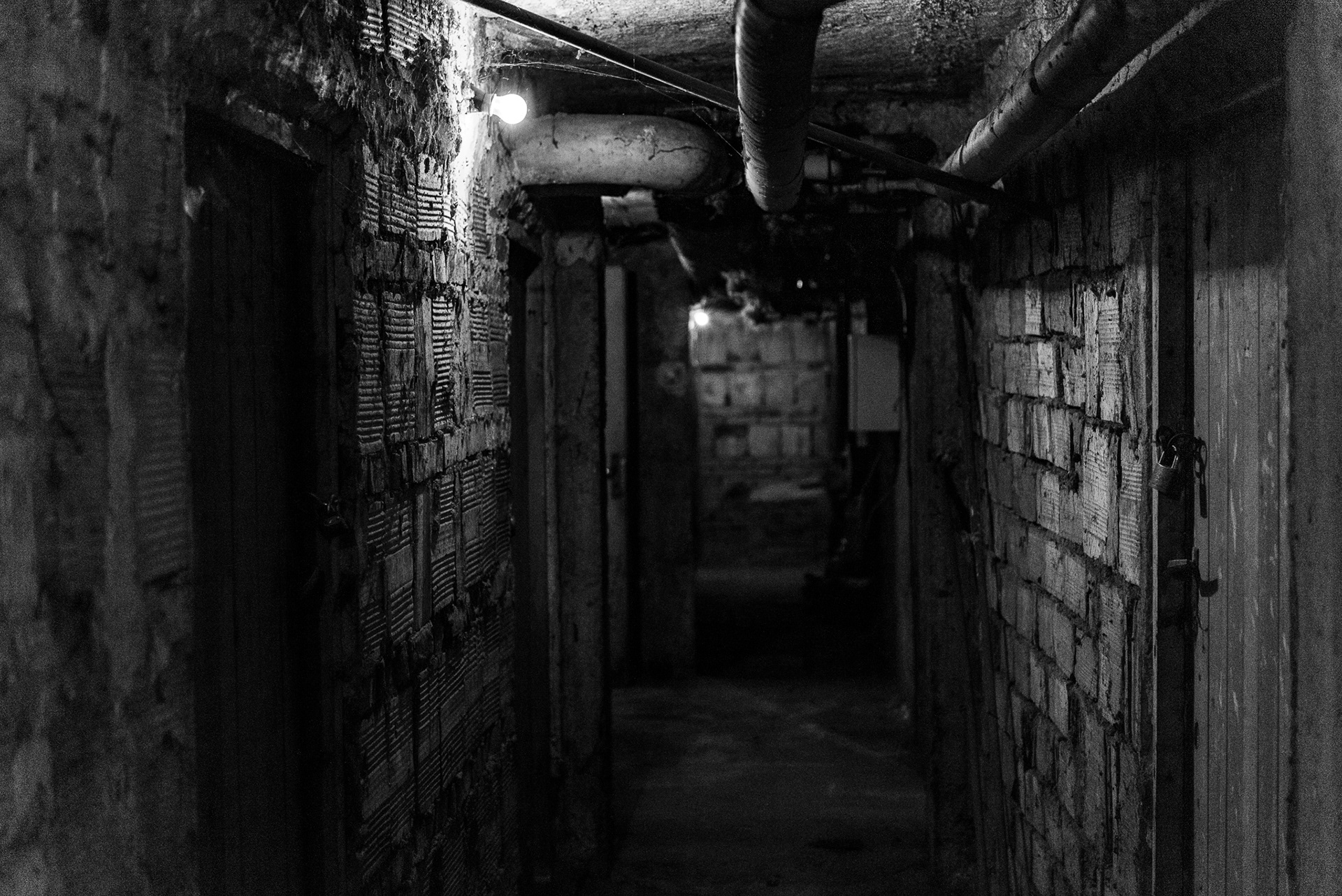

Project MAZE/МАЗЕ explores the space created by the intersection of meanings of this homograph [4] and conceptualizes basements as allegories of our minds.

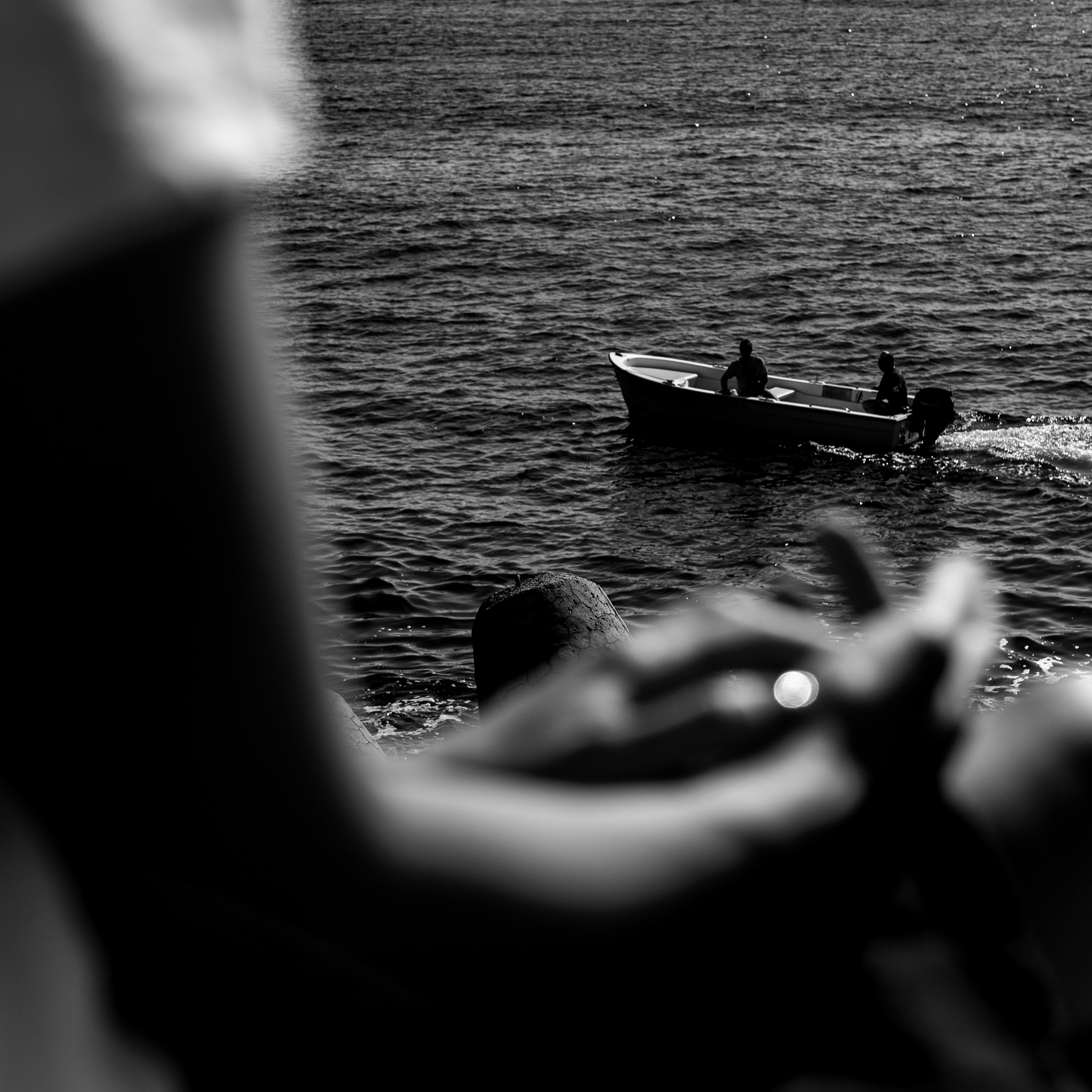

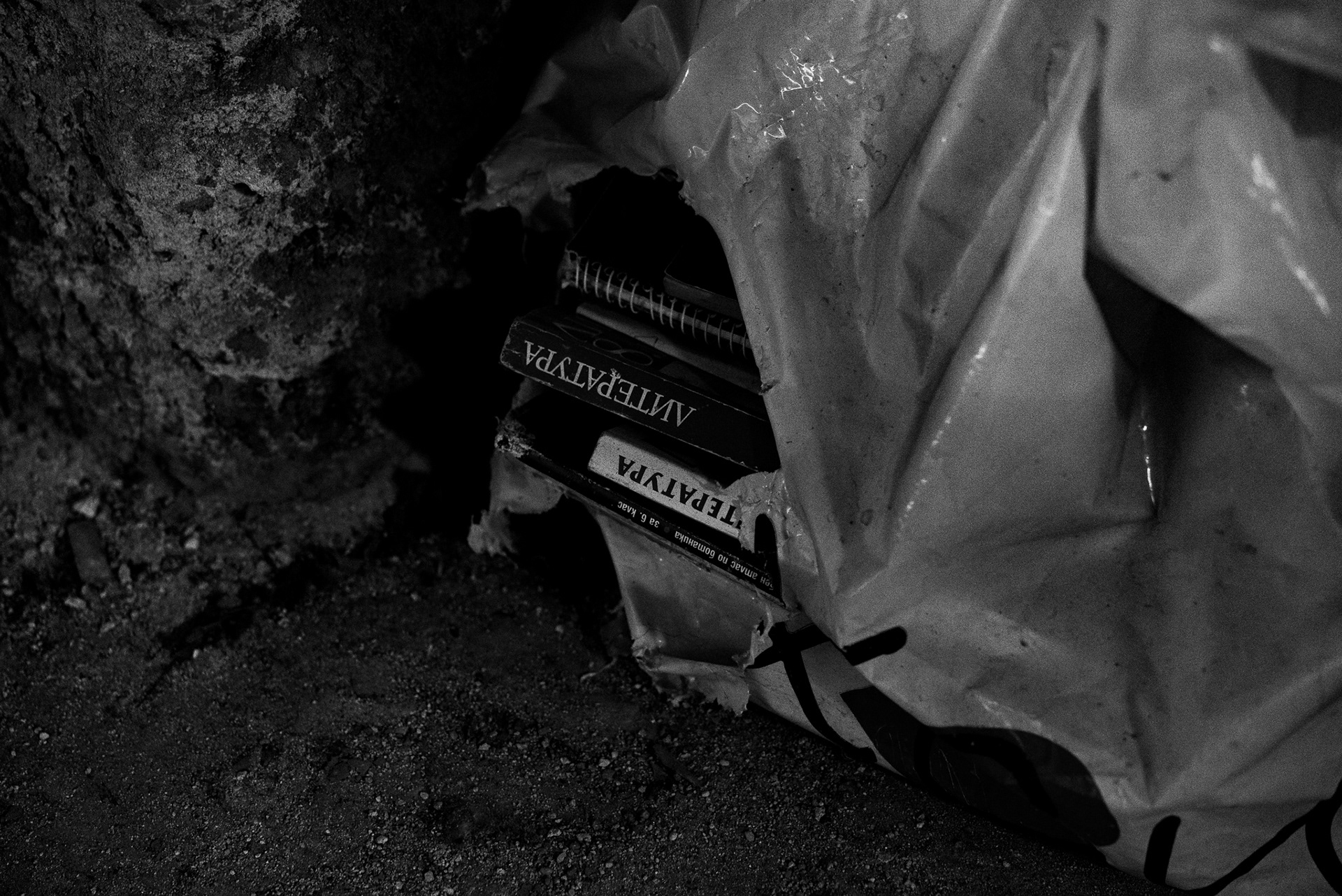

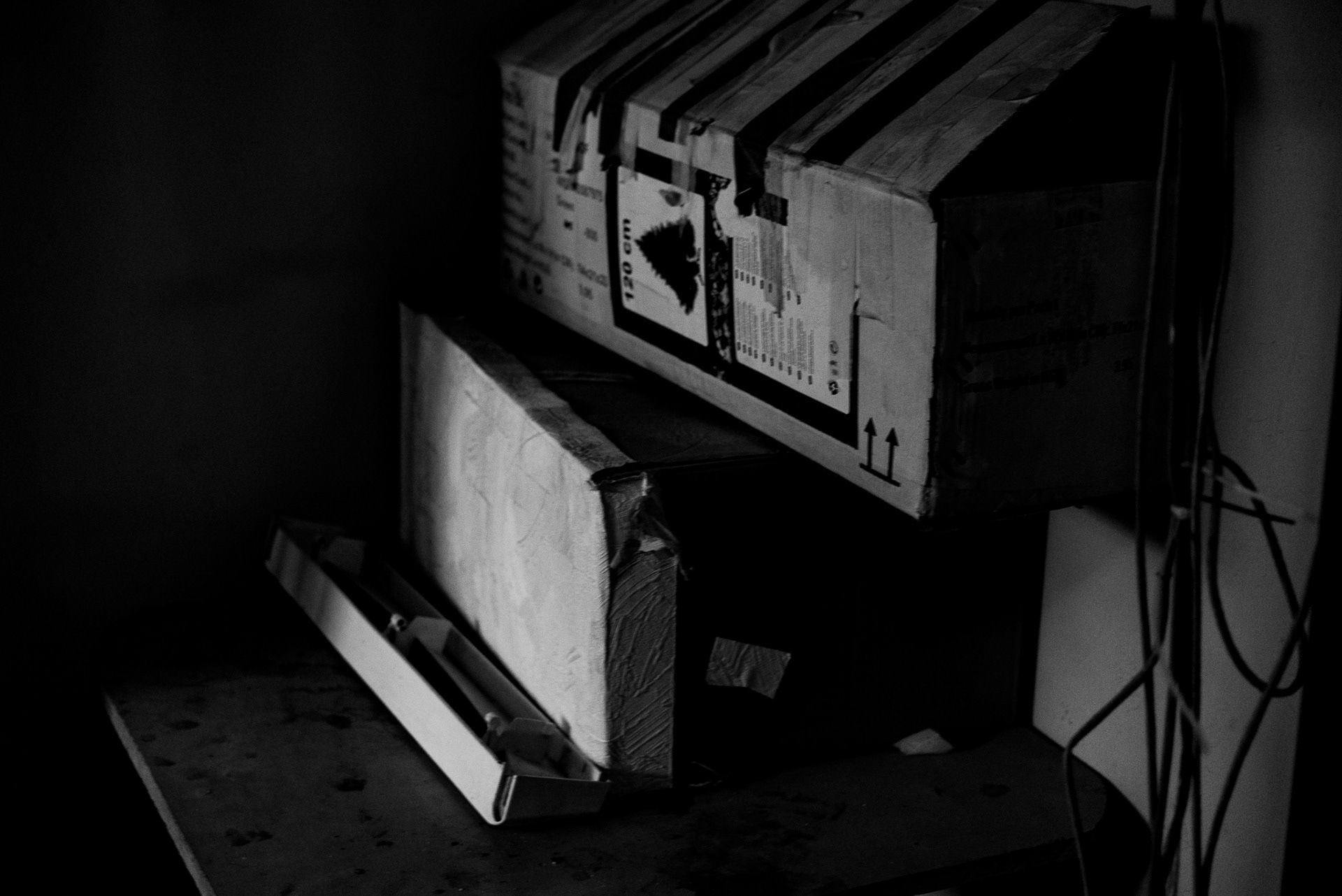

The ‘мазе’ is the territory of the ‘in-case-I-might-need-it’. Literally at the boundary between our living spaces and the earth, it also occupies the metaphorical no-man’s-land between what is in use and what is no longer needed. Basements are places of mental tension. By virtue of their boundary location, their meaning twists and shifts, and is constantly updated and renegotiated. Things come in and go out; what was useless becomes valuable, and things we used yesterday are relegated to the basement. The lowlands of our kingdoms brim with life created in the primordial soup of the sunlit world.

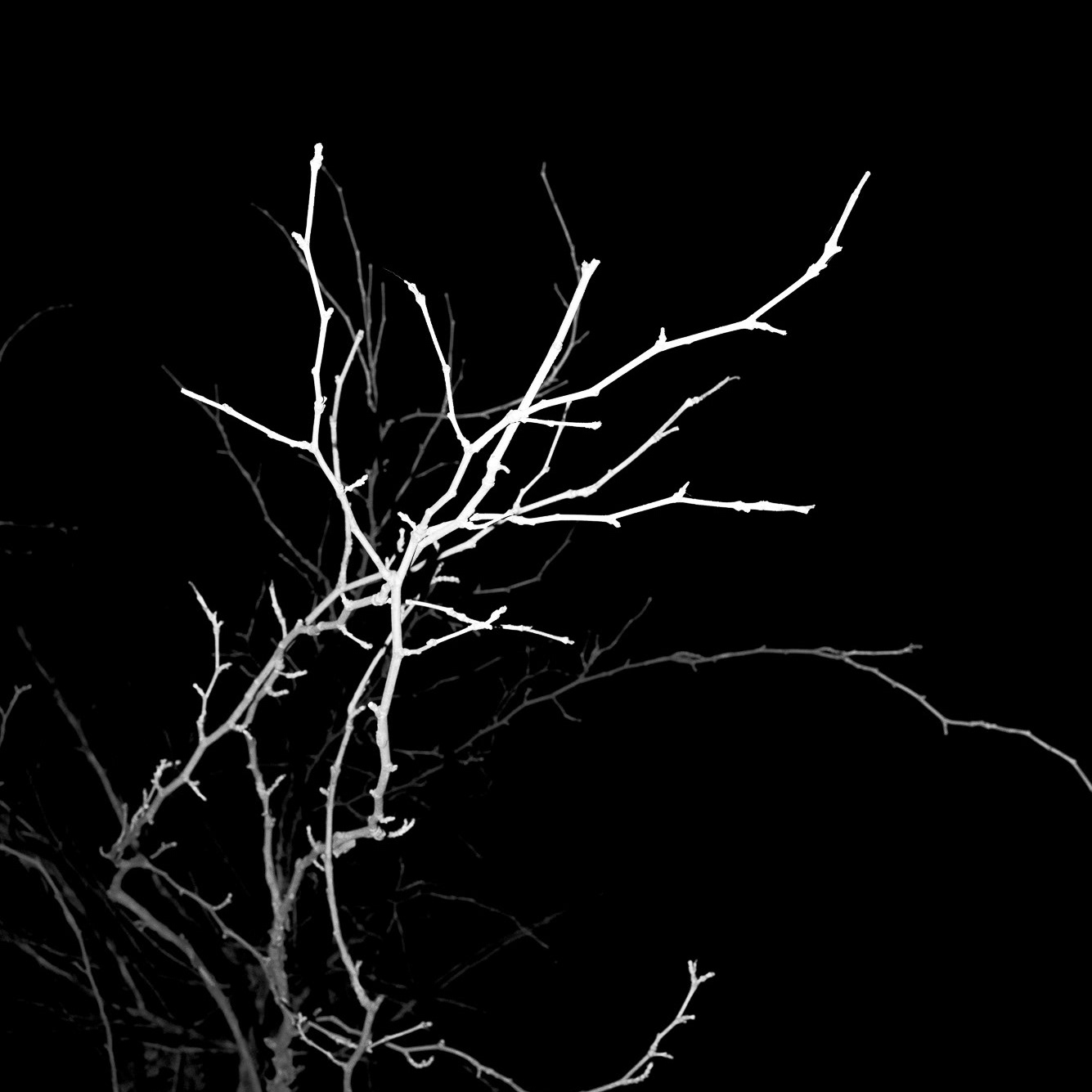

In this evolutionary process, the basement adopts a maze-like quality, “embodying both superb design and unfathomable chaos, its elaborate complexity causes admiration or alarm, depending on the observer’s point of view and sophistication” [5] What was once an empty space becomes a hodgepodge of memories. What once existed for a reason now occupies a location at the brink of our minds and homes. What once contributed to our lives now becomes a close to useless item in a storage space.

The ‘мазе’ is a territory of the ‘almost’: almost worthless, but not entirely; almost rubbish, but not yet; almost inessential, but not quite. Such is the nature of basements and minds alike: “they simultaneously incorporate order and disorder, clarity and confusion, unity and multiplicity, artistry and chaos” [6] For are we not like basements? Collections of scars lurking beneath a shining surface. Things we want to forget, but do not want to let go just yet. A chaotic assemblage of randomness somehow miraculously appearing well-designed and orderly. Aren’t our lives, like basements and mazes, all a bewildering “network of passages” loosely held together by a fragile thread; labyrinths with a single entry point and a single exit, connected by winding and contorted paths?

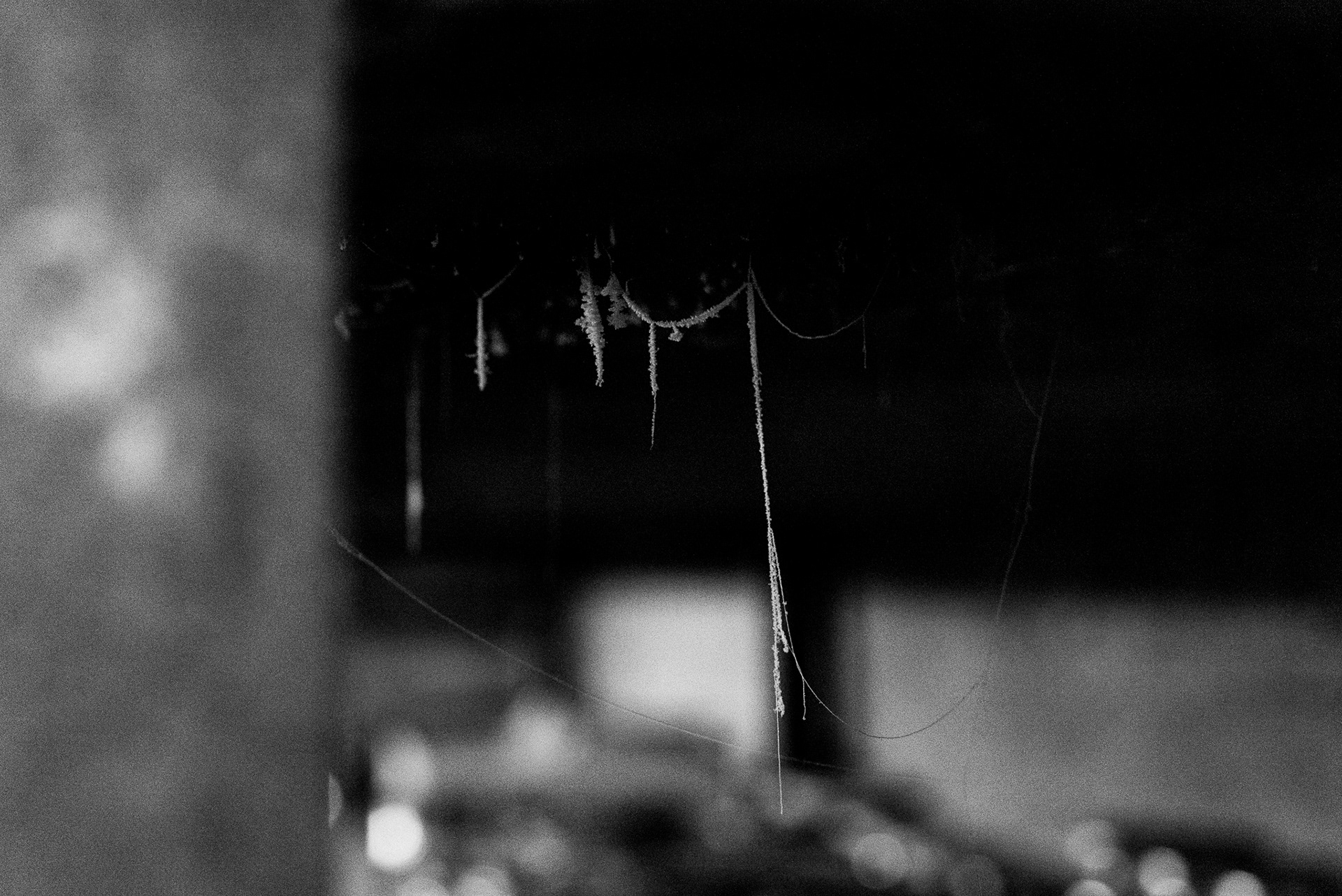

With the advent of the digital age, it seems that we escaped the tyranny of the physical ‘мазе’. We pride ourselves on not being like our fathers, storing useless items in a dusty room below the ground. But because “most perilous prisons may seem most enchanting” [7], we leave the physical ‘мазе’ just to find ourselves entangled in a new kind of wandering paths – the digital ones. Recycle bins, browser histories, bookmarks, apps to set things aside to read or engage with later, and dozens of open tabs all mesh into a maze and create a digital ‘мазе’ full with things we-might-need. We leave the physical webs woven by spiders in our basements to enter the digital web woven by us on our phones and computers.

By exploring the worlds of the physical and the digital ‘мазе’, and conceptualizing them as mazes, this project alludes to the collect-ive nature of our lives. It invites us to think of ourselves as a bricolage of memories and identities, with fragile and precious connections between them. Project MAZE/МАЗЕ uses the physical space beneath our living areas to hint at the maze/‘мазе‘-like nature of our lives – in motion and unchanging at the same time, governed by the ‘almost’, and connected delicately to objects and places and people by a thin thread of cherished memories.

References:

[1] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/maze

[2] https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/maze

[3] According to the rules of transliteration

[4] “… a word that has the same spelling as another word but has a different sound and a different meaning.” homonym vs. homophone vs. homograph : Choose Your Words : Vocabulary.com

[5] Doob, Penelope Reed. The Idea of the Labyrinth from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages (p. 81). Cornell University Press. Kindle Edition.

[6] Doob, Penelope Reed. The Idea of the Labyrinth from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages (p. 16). Cornell University Press. Kindle Edition.

[7] Doob, Penelope Reed. The Idea of the Labyrinth from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages (p. 208). Cornell University Press. Kindle Edition